Has the EU Chips Act Failed Before it's Started? Industry Strategy Symposium 2023

The big theme at this year’s SEMI Industry Strategy Symposium (ISS) conference was ‘How does Europe fulfil its ambition by 2030’. Jamie Potter shares his thoughts on the steps being taken to achieve its ambitious goal.

The big theme at this year’s SEMI Industry Strategy Symposium (ISS) conference was ‘How does Europe fulfil its ambition by 2030?’. It involves an ambitious target of reaching a 20% share of the global semiconductor market by 2030 whilst having a more resilient industry ecosystem. This is a huge challenge, especially when one considers that the global semiconductor market is forecasted to reach $1tn by 2030. A 20% share of this would mean $200bn in just seven years. For perspective, the global market figure currently sits at $600bn which means Europe’s present-day 8% share is around $48bn. Breaking it down like this reveals the magnitude of the challenge; Europe must increase its share of the market by more than quadruple as the size of the pie increases along the way. Looking solely at Europe’s rate of growth in the market over recent years compared with the rest of the world, I can tell you that their target is infeasible. But before we conclude, there are several aspects to consider.

First, what is going to drive this extraordinary growth? Second, why has the EU – and indeed the US which currently claims 10% of global semiconductor manufacture – set these targets? And finally, what is being planned to achieve them.

- Semiconductors are a major driving force in the global economy and the EU clearly recognises this, but perhaps not to the full extent. Almost every modern innovation utilises electronics in some form or another, with the obvious mega trends over the past few years being computers and smartphones. Looking forward, applications that are likely to drive demand further include smart mobility, 5G, AI, IoT, quantum computers, 6G and so on. All of them need increasing amounts of leading-edge chips to handle everything from data capture to cloud processing in order to enable devices and systems to make smarter decisions.

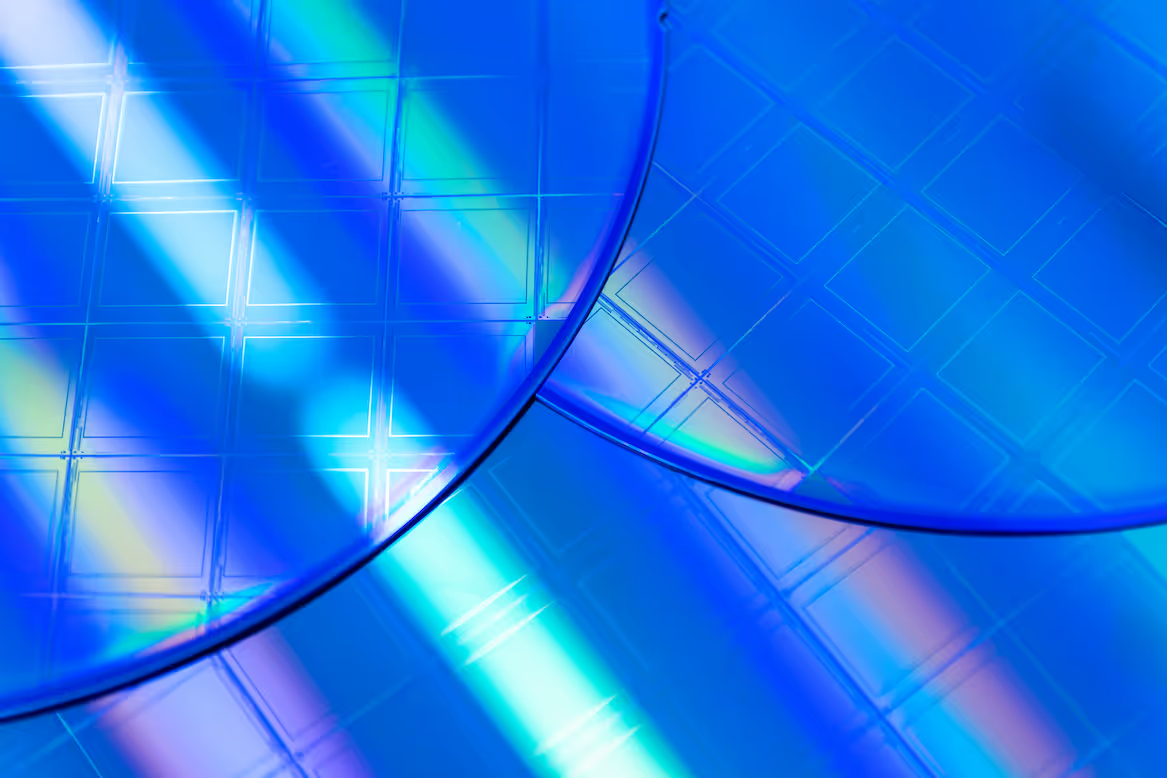

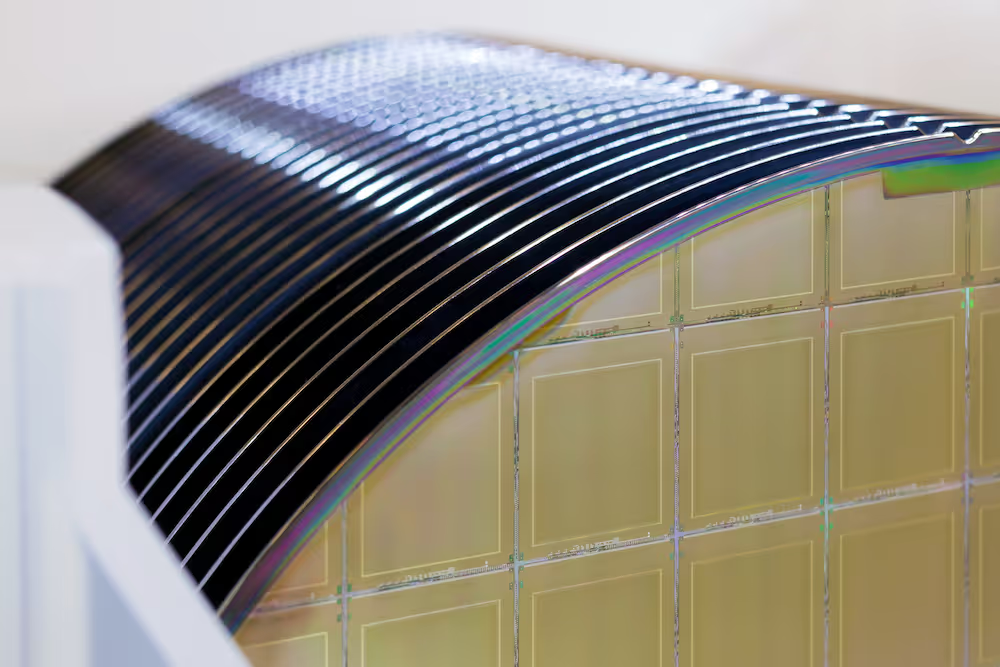

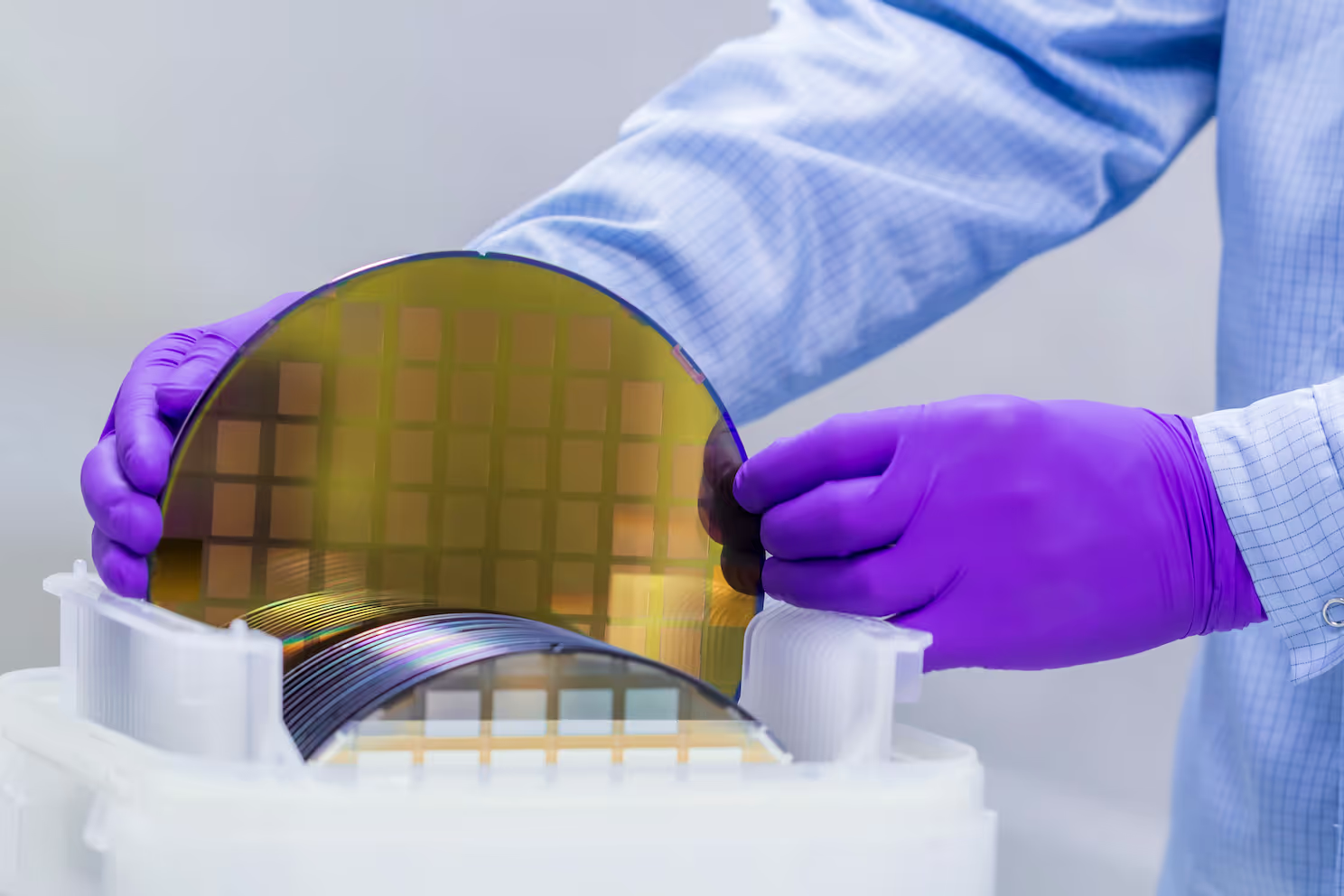

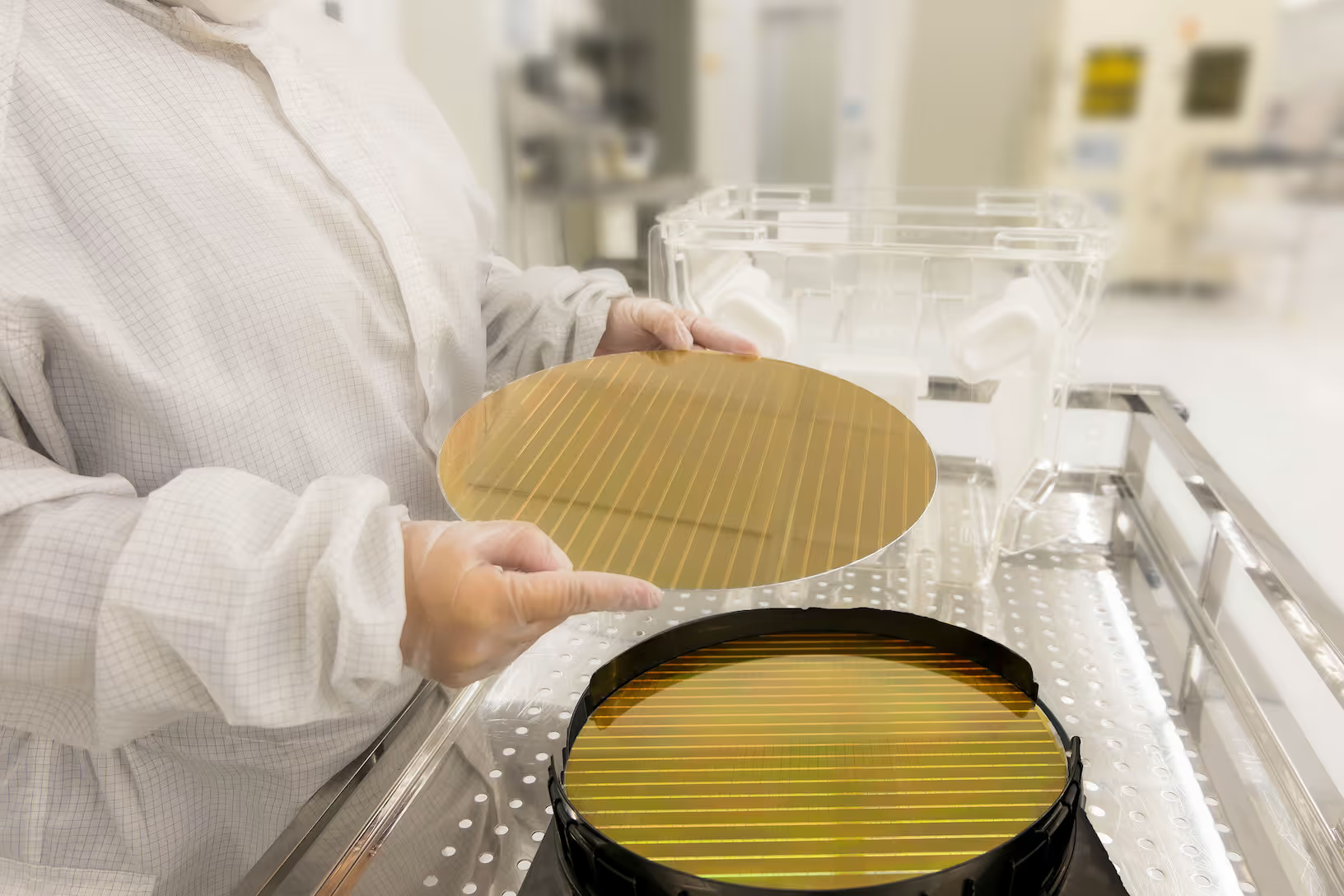

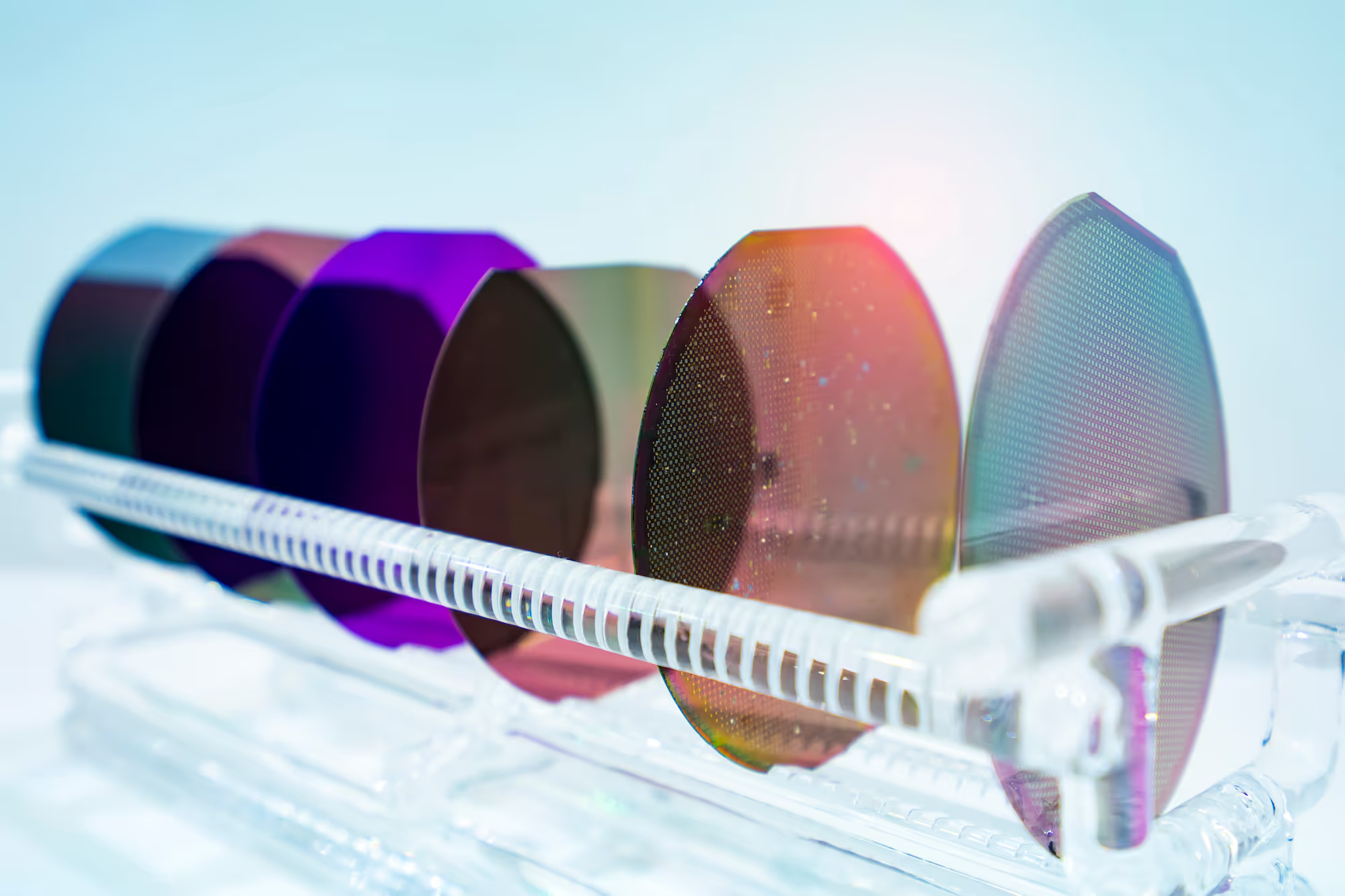

- For years we have been enjoying a tightly integrated, global supply chain with wafers and chips crisscrossing the globe as the journey from silicon wafer to packaging to test is done in stages in centres of speciality in different countries.

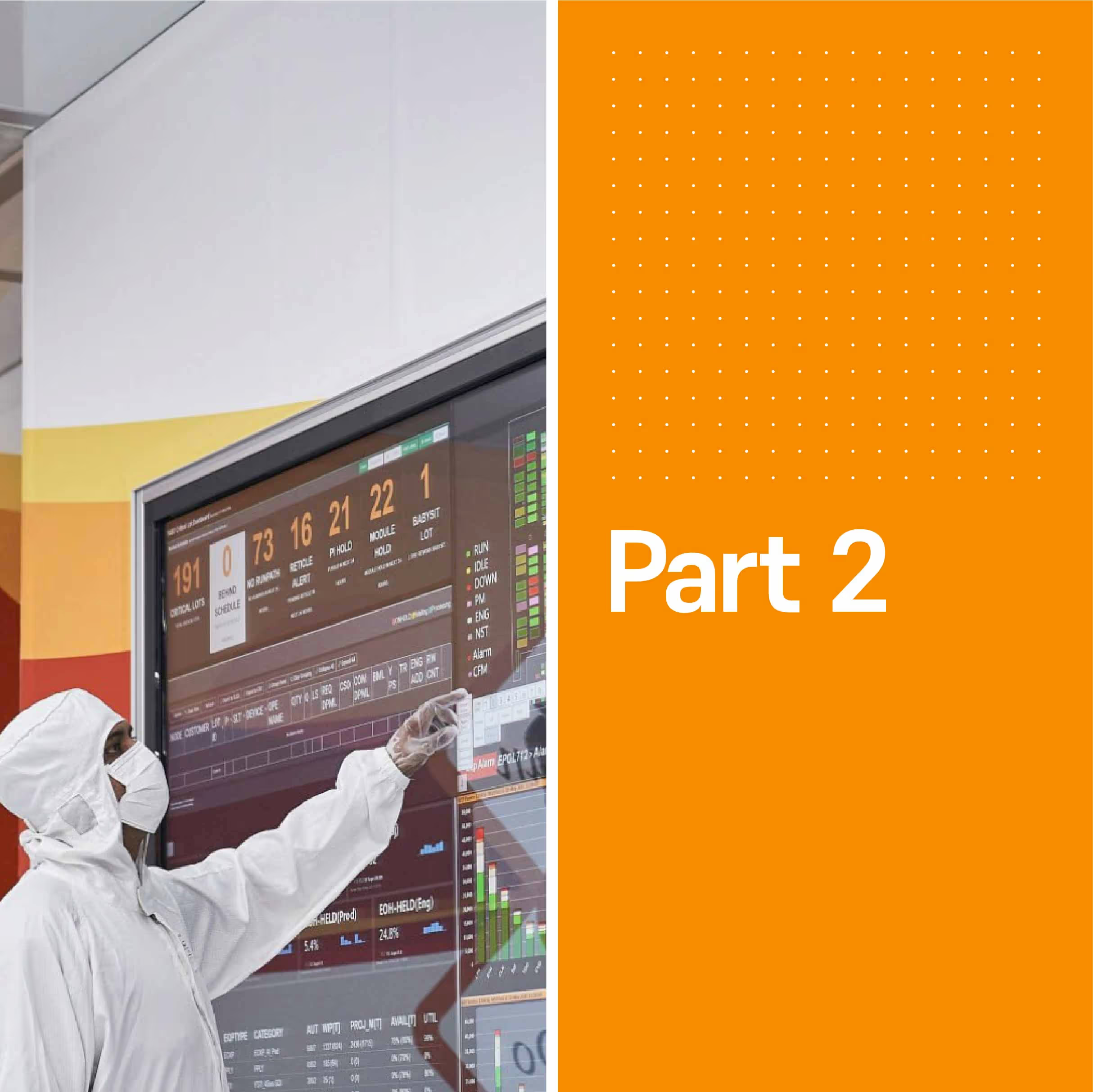

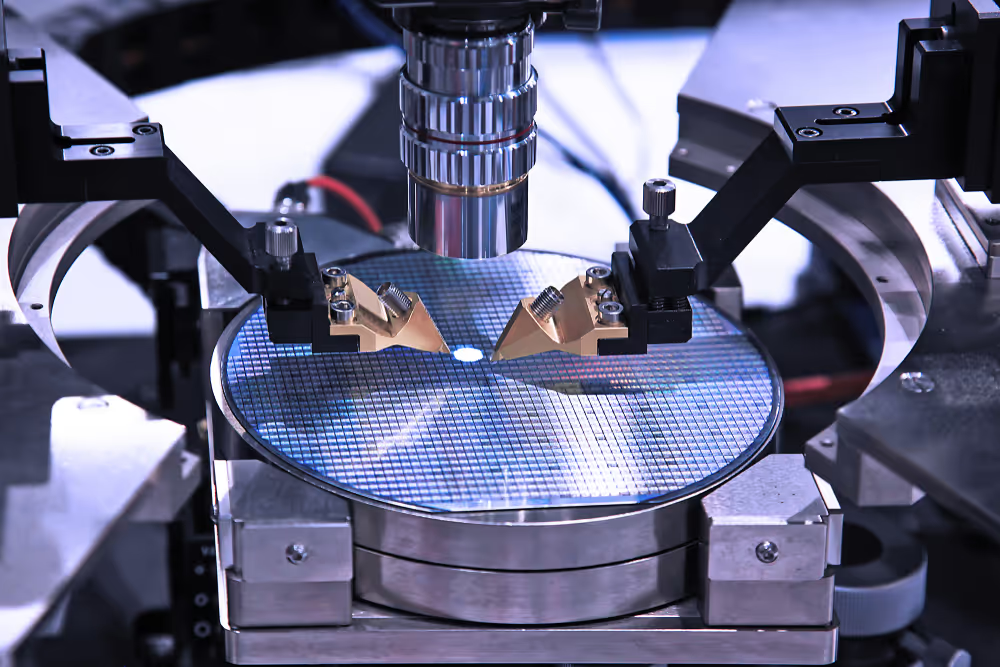

Covid and the ongoing geopolitical tensions between the US and China mean that this model is being redefined to be more robust. The ideal solution is to onshore all stages of the manufacturing process, i.e., keeping it all within US borders or within EU countries. Thus, these targets don’t intend to take a larger share of the global manufacturing pie. Instead, they aim to increase the amount of semiconductors manufactured that aren’t sent overseas to provide resilience against disruptions to the supply chain of these devices, which are essentials for a healthy economy. China is already on their way there. They currently make 16% of their chips onshore, with ambitions to increase this to 70% in the future – highlighting massive potential growth in this market. - Semiconductor manufacturing requires wafer fabs. The vast majority of fabs today are in Asia, with big players such as TSMC, Samsung and UMC. The challenge with these ambitious targets is that building a new state-of-the-art fab for today’s advanced nodes takes billions of dollars, requires a skilled labour force and takes several years to build once planning permission is granted. And then there are all other stages of packaging and test facilities to be built from scratch and staffed. The skilled labour needed to manage this doesn’t currently exist in the EU so it’s clear to see how setting up totally onshore manufacturing capabilities will take considerable time, money and expertise.

Expertise can be fast tracked by partnering with existing fab companies; such as TSMC discussing building new fabs in the US and Germany. But naturally, they require government grants from the funds being created to boost the semiconductor manufacturing industries. It’s worth comparing how much each area is allocating for this. South Korea’s figure is $450bn, the US is $233bn, and China is investing $200bn. With these sizable sums already formally approved by the relevant authorities, fab construction in these nations is already starting.

The EU, on the other hand, is only planning to invest a comparatively tiny $43bn.

This figure is nowhere near enough to quadruple its current semiconductor manufacturing capabilities. In fact, Kurt Sievers, CEO of NXP, estimated that a more realistic figure to achieve a 20% market share would likely be over $500bn. And moreover, this has not yet been passed in parliament, so the EU is already behind on the timeline to achieve its target compared with the other market players. As for the UK, the figure has not been announced but is rumoured to be around $1bn – which is not enough to fund just one new fab at an advanced node.

It’s important that SEMI is driving this discussion around the EU Chips Act as government funding is a critical driver for the region's growth within the global semiconductor market. But it’s not enough. As an industry, we need to take stronger action and challenge the decisions being made by the EU and the UK. They require the expertise of industry leaders to understand the full importance of microelectronics for the economy, without it I believe the money they invest will be fruitless.

As regular readers know, our software can make existing and new build fabs smarter and substantially more productive, but in order to hit the EU’s extraordinarily ambitious targets, more funding and strategic partnerships must be considered. I suspect that one solution will entail a close relationship between the EU and the US to create a US/EU-based supply chain model with both regions working together to share their centres of excellence to create a complete, self-contained system. Even if the ambitious targets are not met, working on de-integrating the supply chain with onshoring will provide security for the electronics that underpin today’s successful economies.

Author: Jamie Potter, CEO and Co-founder of Flexciton

Photo Credit: SEMI

More resources

Stay up to date with our latest publications.

.avif)

.avif)

.avif)